How to organize time for online instruction. Are there differences in relation to in-person instruction?

Current experience with distance learning (up to November 2020) shows that students significantly lack feedback, contact with classmates and the instructor, and the opportunity to personally solve larger and smaller issues that were easy to handle during in-person instruction.

We, therefore, recommend the following for online instruction:

- Include as much feedback as possible.

- Assist students in finding and addressing the most difficult areas relating to course materials; this includes, in particular, acquiring competence in solving real or simplified problems in the field in which they are to become professionals on the labour market; many disciplines suffer from the elimination of practical training.

- Promote the healthy self-confidence of students by preparing them as they learn to handle difficult situations with our assistance.

- Ensure that students do not give up on the quality of their education.

Preparations from the pedagogical perspective

Below is a short checklist and possible solutions to typical situations:

Simple instructions for scheduling and joining online courses

Question: Do our students know when and where to join a class? Is it clearly indicated in the study agenda or, for example, in the Moodle course? What if instructors take turns during the semester and each of them teaches a different day or week in a different virtual room?

Tried and tested functional solution: For an entire subject (course), we prepare in Moodle an overview of all teaching units (lectures, exercises, seminars), where the date, time, and the link to join the course is clear. We will contact students from a specific year to go through this preparation from their perspective and with their rights to the specific platform and have them inform us if everything is clear and comprehensible for them. There must be no doubt as to where, when, and how each lesson takes place. In each year of study, there will be students willing to work with us in this manner and with whom we have a common interest, i.e. so that the instruction runs as smoothly as it should

Instructions for preparing students for a class

- Question: Do students know if they should prepare for a specific lesson in order to be effective for them? Or will everything be communicated to them in the lesson only?

Tried and tested functional solution: If we design the instruction in such a way that it requires students to prepare in advance (e.g. read a text, watch a video for discussion,…), let’s assume that it will take several hours before we get a sufficient number of students used to this system. We provide the necessary materials in time in the Moodle course. During the actual lesson, it must be obvious what advantage those students who followed our instructions have.

Feedback, diagnostic and formative evaluation during instruction

- Question: Do students know during the semester and do even we, as instructors, know if the material covered was actually understood? Do students have the feeling that they are “keeping up” only to find out during an exam that they were wrong? How do we, as instructors, find out if what we were trying to convey was really understood and that we can continue with the instruction?

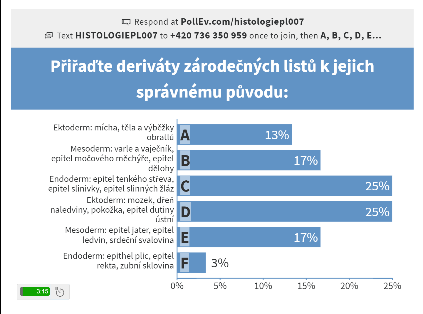

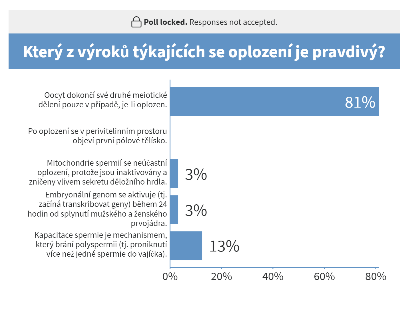

Tried and tested functional solution: At the beginning of each lesson, we will give a short quiz which the students who actually understood everything should pass. We ask not only about banalities, which can be easily Googled, but rather about the conceptual issues that require a deeper understanding, an ability to make judgements, prioritize, draw conclusions, make decisions, etc. The quiz takes place mainly in diagnostic evaluation or formative evaluation mode (see the glossary), i.e. it is a relatively safe space for students without being associated with the grading process at a later stage. We encourage everyone to get involved, we do not insist on immediate answers, and we reveal the results only after providing a time for contemplation – i.e. we prevent the frequent situation where only the same handful of the most motivated individuals answer the tests, while the rest of the students are passive. The platforms polleverywhere.com, socrative.com or mentimeter.com are suitable for these quizzes. If most students are able to solve the problems, we only quickly comment on possible mistakes in a positive spirit and we move on to the next subject. If we find that the students are unable to solve the questions that they should theoretically be able to answer, we offer explanations in reserve, analyse errors, and fill in the knowledge gaps. We can also think about why it happened and how to prevent this next year. In any case, we will create a good habit for students in the sense that we all take teaching seriously, that we identify problems in time, and solve them, which is in our common interest.

Clear conditions for passing a course

- Question: At the beginning of the course, were the students demonstrably acquainted with the unambiguous conditions for completing the course as a whole?

Tried and tested functional solution: In SIS, and possibly also in the introduction of the Moodle course, in which we have the syllabus for the whole course, we have added achievable and clearly verifiable conditions for granting credit or for passing the exam. We verify by asking the students if they have understood the conditions, thus avoiding a number of possible problems, speculation, or complaints during the examination period.

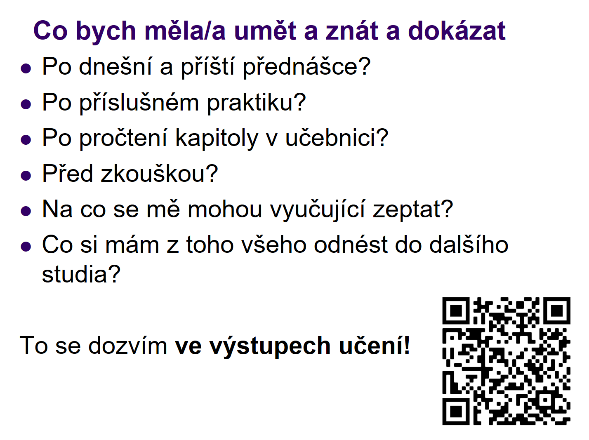

Learning outcomes

- Question: Do we as instructors have a clear idea of what students should be able to define, solve, calculate, discuss, compare, estimate, decide, and propose… (complete according to the competencies of the students who took your course) at the end of a course? Do the instructors of related courses or the employers of our graduates know what knowledge or skills our students acquire?

Tried and tested functional solution: We first make sure that we do not confuse the learning outcomes (a list of verifiable, achievable, measurable, unambiguous, public, and comprehensible assignments that we are satisfied with after completion; see glossary), for example, with the syllabus (what is the content of the course and what we try to teach students). Especially during a period of distance learning when students can search through a wide range of study materials, what they should KNOW at the end of a course must be clearly determined. It is NOT the same as what we tried to teach our students.

Learning outcomes are, of course, important not only for distance learning, but for any type of instruction. Preparing them can be a difficult task, but there is no substitute for them. The following table summarizes the advantages and disadvantages of having or not having learning outcomes.

| When we have learning outcomes published for our course/subject | When learning outcomes are not prepared or published |

| From the perspective of instructors | |

| A clearly written document where the instructors had to agree on what they would actually want from the students and how they would test them on this. | Each instructor can require something different from the students. The validity of testing is then compromised. |

| New instructors for a course know what they should require from students. | It can take several semesters for new instructors to be able to prepare their students well for passing a course and taking exams. |

| The rich pedagogical experience of experienced examiners who know very well “what to ask” is applied here and preserved in writing. | It is difficult for new instructors to apply the experience of other examiners. |

| A clear guide on how to effectively spend time relating to instruction. | “Saved work” in the absence of learning outcomes leads to confusion as to what is worth including in a class and what is not. |

| The feeling that we teach according to instruction based on evidence (evidence-based teaching, see glossary of terms). | Teaching according to principles other than those supported by thoroughly verified and published studies is difficult to defend. |

| Opportunity to compare with foreign and international courses, where learning outcomes are commonplace. | Unclear compatibility and comparability with foreign instruction of my subject. |

| An answer for instructors of related courses if they ask “what are your graduates capable of?” | Difficulty in answering this question. |

| Shifting attention from “what we teach” to “what our students know.” This is not the same. | How do we deal with the absence of a document describing what our graduates are capable of? |

| Compiling tests and exam questions is relatively easy because it follows directly from the learning outcomes. What is to be the basis of the evaluation must be important for the subject area – and what is important should not be concealed. | The composition of test is difficult to justify. If they are not based on defined learning outcomes, what are they based on? Instructors surprise students during exams, i.e. they ask about things that students are not expecting and are not prepared for. |

| We show students what is really important from the entire course. | We leave students in uncertainty about what really matters. |

| Opportunity to look at the learning outcomes of related courses | There is no easy way to find out what new students know. |

| From the perspective of students | |

| I know what I have to learn and how my work will be graded. | I am unproductively stressed out about what may or may not be included in tests and evaluations. But because I’m still interested, I’m wasting time and nerves with speculation and rumours on the subject. |

| I can verify before an exam if I am prepared to take it. | Sometimes I do not find out whether I have met the requirements of the examiner until I take an exam. |

| I try to find my way through the flood of resources and materials and choose from among them what is really important. | I study with the risk of devoting energy to irrelevant and marginal knowledge, and I do not have time for what is really important. |

| From the perspective of faculties or guarantors | |

| Thanks to the conciseness of learning outcomes, it is possible to map out the curriculum, especially the interconnection of courses, possible “white spaces” that no one teaches and tests, or, on the contrary, duplications. | It is almost impossible to map out which requirements students must meet within the study programme or subject area as a whole. |

| It is a mandatory part of all accreditation. We fulfil it with a document that also has content and meaning for us. | We provide documents of little value for accreditation just to comply with the bureaucratic requirements. |

| The constant refinement and updating of these public documents prevents the curriculum from being stagnant. | A risk of making instruction obsolete or its disengagement from the needs of employers. |

| Great advertising. An internationally comprehensible document demonstrating “what our graduates are capable of” and “how we know that they have actually learned the materials”. | As a student considering where I would like to study, I would consider whether I would want to connect my destiny with a subject area or discipline that does not have a detailed written description of what the results of each specific lesson are and what I will be able to handle as a result of the requirements and tasks after completion. |

Summative evaluation and grading with the use of PC tests

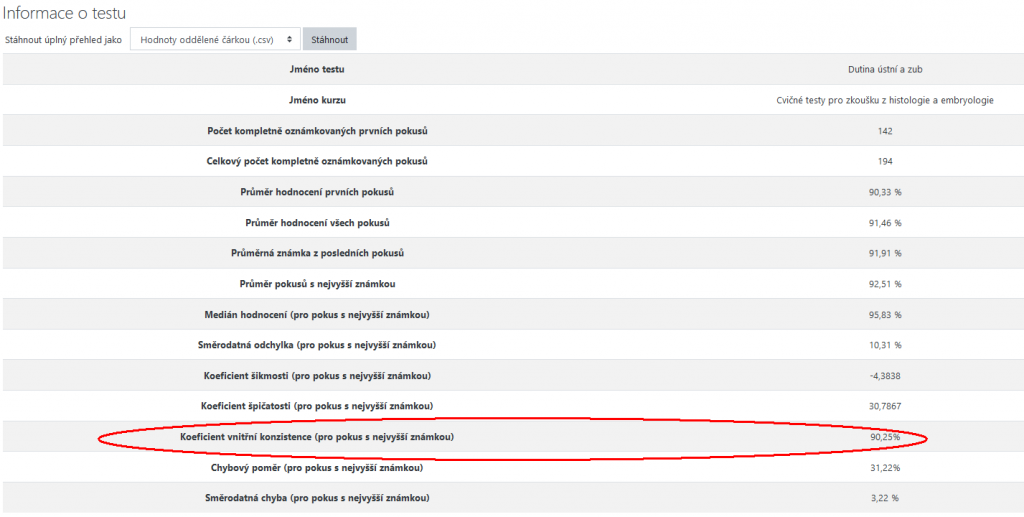

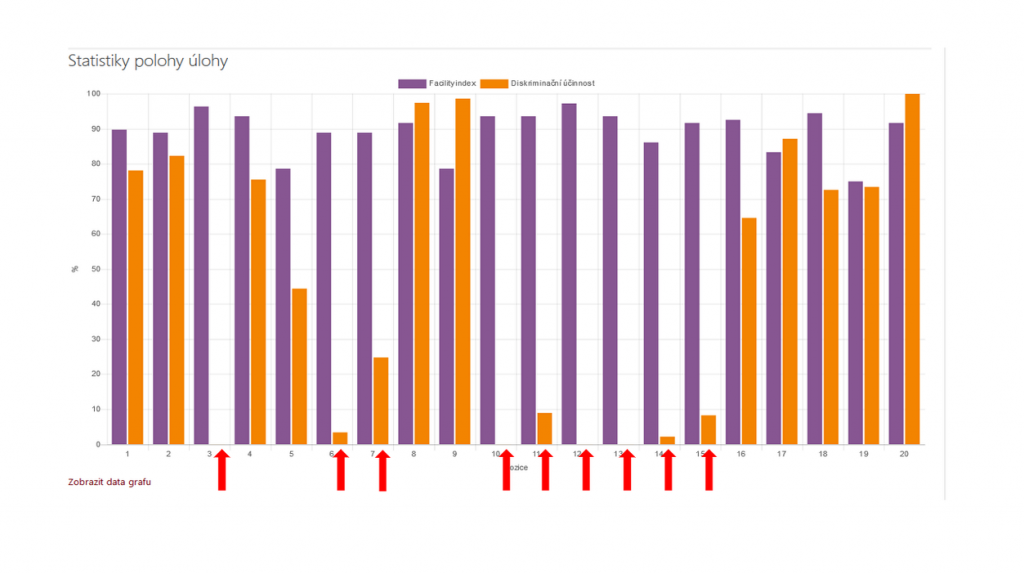

- Question: If we use any form of tests for grading, do we have any measure of validity? We carried out an analysis of the individual test items (questions), and do we know the facility index and the discrimination index for each of them? How do we find out if the test is not enough, sufficient, or too much? Are the different test variations comparably difficult? Are we testing what we really require of students in their learning outcomes? Have we prepared students for what they will be actually tested on?

Tried and tested functional solution: After collecting a sufficient number of answers in our tests in Moodle (e.g. more than 30 for each question), we calculate the statistics below (see also the glossary – test reliability; test item analysis; facility index and discrimination index of for test questions). If the topic is new to us, we review, for example, the reference manual Štuka, Martinková, Vejražka et al., Karolinum, 2013).

We also make sure that our tests examine the knowledge and skills declared in advance in the published learning outcomes. We reduce speculation and stress caused when students do not know what to prepare for, how their academic success will be assessed, and what exactly they should know. The validity test is compiled over precisely formulated learning outcomes, which are available to all instructors and students. There is no discussion about what belongs in the test and what does not, because it directly tests specific, achievable, and measurable learning outcomes. There is no convincing evidence that hiding students from the tested competence would somehow contribute to their academic success or employability on the labour market or strengthen good study and work habits. To have a fair and transparent system of grading that motivates students to properly master the curriculum and learning outcomes, the whole testing process must be set up in a demanding but manageable manner (without cheating!).

Students positively evaluate if they have practice sets of tests at their disposal and which they can verify in the form of self-study whether they understand the materials and whether they are well prepared for the “real” graded tests. It is a significant advantage if the workplace has such a storehouse of quality questions that can be shared. If there is only a small set of questions available, there is usually concern that publishing them would degrade the PC test to an inappropriate status. If students cannot practice the questions or if the correct answers are not made available to them after the test, the instructional potential of the tests remains untapped. Experience shows that students actively seek out (or even require) self-testing and learn a lot thanks to the tests. In addition, the strategy of concealing test questions is not very successful in the long run, and in reality, leads to spontaneous and unauthorized dissemination of inaccurately reproduced questions that previous test-takers remembered with no guarantee of accuracy and often with confusing errors that are difficult to eliminate in hindsight. This particular situation is not beneficial for instructors or students.

Summative evaluation and grading based on oral testing

- Question: Are we asking students and demanding from them what we have declared that they are able to do in the learning outcomes document? Have we prepared students for what they will be tested on, or are we surprising them with materials they encounter for the first time during an exam? Are the questions and supplementary questions asked by the various instructors comparatively difficult? Were we able to distinguish in instruction what is really important and therefore should be the basis for grading, or do students struggle and feel surprised?

Tried and tested functional solution: We make available to students the “learning outcome” document. Assignments are presented here, and after completing them, we consider students to be capable of passing the course. These results are written and formulated as verifiable, achievable, measurable, and unambiguous. They are approved by the guarantor, are publicly available to all instructors and students, and are binding for both parties. We verify that they are clearly formulated for the students. Well-formulated learning outcomes on a specific topic can be used directly as test questions. If something is so important that it is to be the basis for grading, it cannot also be used as a “secret bargaining chip” of an examiner. There is no convincing evidence that hiding the tested competence from students would somehow make a positive contribution to their academic success or employability on the labour market or strengthen good study and work habits. On the contrary, students’ energy should be directed to effective preparation for fulfilling the demanding but clearly declared assignments. There is no need to worry that this would degrade university instruction to a kind of thoughtless “catechism” of pre-selected questions and answers or that this practice would distract students from a more profound understanding. Evidence of the effectiveness of instruction (for more details, see the cited literature) says quite the opposite. To this end, one must ensure that the assignment of learning outcomes is balanced in the spirit of Bloom’s taxonomy (see the glossary), testing in a balanced manner knowledge memorization, understanding, use of knowledge and skills in problem solving, the ability to analyse problems, to evaluate and synthesize them, and also creating new values and complex decision-making.

Changes to the strategy of distance testing in relation to in-person testing

- Question: How does one ensure the fairness and transparency of distance testing and prevent cheating when students are physically out of the reach of examiners?

Tried and tested functional solution: Technical options to make it difficult to cheat and use illegal resources and aids during testing include identifying students in front of a camera with a photo ID card, not allowing virtual backgrounds, and the organization of students’ desks and immediate surroundings so that there are no unauthorized items or devices. Another option could be to shorten or limit the preparation time so that there is no possibility of unauthorized items. In addition to these technical options, it is also important to evaluate the entire examination settings and philosophy, se that we can at least reduce the probability that students will be motivated to cheat. Under no circumstances should cheating be an advantage. We can, therefore, use the transition to distance testing as an opportunity to re-evaluate or modify our testing strategies. For example, you can limit those parts of the exam where the answers can be easily copied, answered, or googled, which is usually just a simple test of memorized knowledge. However, if we shift the focus of the exam to the higher levels of Bloom’s taxonomy (see the glossary), i.e. instead of testing knowledge, we test the ability to analyse resources, solve a specific problem, find information needed to make decisions, design and compare the advantages and disadvantages of solving problems, decide according to rules known to students, or draw conclusions about certain data, we test and grade already relatively complex procedures where it would not be easy to deceive the instructor and examiner or to use illegal aids and devices. In an extreme case, it could be an “open-book exam”, which mimics the solving of practical problems in the student’s discipline where there is a time limit for answering questions and submitting solutions to the problem, but the use of resources is not limited. On the one hand, this strategy corresponds to reality in which professionals in the field can usually check on their procedures and decisions using the Internet. However, an unprepared student who does not have the necessary procedures and knowledge base and tries to compensate for their unpreparedness by frantically googling has no chance of completing the task in time. With such a change in testing philosophy, instructors would be expected to invest a considerable amount of time on preparing and creating appropriate assignments.

Maintaining the level of distance learning in comparison with in-person instruction

- Question: It is possible in distance learning and testing to at least come close the level we were accustomed to during in-person learning?

Not yet verified but possible solution: Restricting the physical presence of students in workplaces that emphasize practical training or restricting work in laboratories (often very expensive facilities) or in the field has significant implications that we cannot completely prevent. In this case, we should notify students if they have missed something important, with a recommendation of when in the future this lack can be resolved or substituted. However, in other parts of instruction, we can at least approach the quality of in-person instruction if:

- We have instruction and testing based on quality learning outcomes.

- We make full use of synchronous distance learning and do not refer students only to self-study. We use asynchronous distance teaching only to the extent necessary (e.g. instructors of clinical medicine disciplines who are also in charge of patients; overloaded instructors who substitute for sick colleagues, etc.). In other situations, we strictly adhere to the course schedules, and at the time of instruction, we are available for our students as if we were in a period without restrictions.

- We provide students with a formative evaluation during each lesson so that students and instructors can promptly identify any shortcomings in education and correct them.

- We do not waste time, attention, or effort with banalities. We make the maximum amount of resources available to students in advance. We do not waste time communicating information to students during lessons – we use electronic courses, pre-recorded videos, etc. to effectively communicate information.

- Instead, we will use the maximum amount of distance learning time to help students understand the most difficult areas of our disciplines. We devote the most time to the most difficult areas – typically, for example, the ability to solve problems, applying learned materials, making qualified decisions, etc.

What do we really spend our teaching time on?

- Question: If we feel pressured when we fail to fit the content of earlier instruction into the structure of distance learning, do we know what the use of our time in distance learning really looks like? Do we know what students and instructors do during this time? Does this correspond to our idea of time effectively used? Do we waste time on something that could be solved in another way?

Tried and tested functional solution: We ask another instructor or student volunteer to take the teaching activity protocol (such as this internationally standardized version of a Classroom Observation Protocol and a stopwatch and to actually evaluate what the instructor does and what the students do during a lesson. The results may be surprisingly different from our intentions, but it will suggest a path towards correction.

What to start with, what to stop, and what to continue?

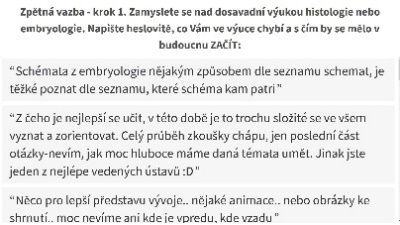

- Question: What are students missing in our instruction? What are they not satisfied with? And what do they like and what should be promoted?

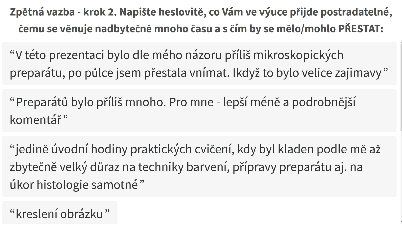

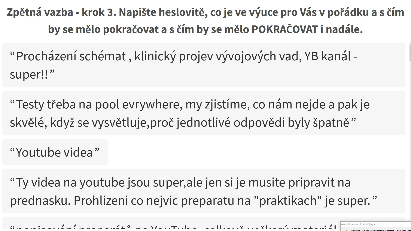

Tried and tested functional solution: Be aware that consistent preparations for distance learning will be quite a burden and will be exhausting. They can be much more involved than in-person instruction, which we were used to and had ample opportunity to adapt to. Nevertheless, let’s try to find the strength for occasional feedback and ask students what to start with (what are they missing?), what to stop (what is unnecessary for them?), and what to continue (what works well for them and deserves to be kept? ). The appropriate timing could be, for example, after a third or a half of the class time when students have already had the opportunity to get acquainted with the teaching regime of the instructor and to see what the teaching entails and what it is like to complete the course obligations. Nowhere is it written that we have to always satisfy the students. This is not even possible, for example, because of a conflict in requirements or because it would have unintended negative consequences for students. On the other hand, there is usually a number of functional and constructive proposals in this feedback that can be implemented. This will strengthen students’ co-responsibility for the quality of their education.

In conclusion, what can we hope for?

Both effective teaching and instruction (from the standpoint of instructors) and effective education and learning (from the standpoint of students) have their own logic. In research and academic activities, academics and researchers do not have difficulty acquiring new knowledge and technology, even at the cost of considerable time and money (instrumentation, consumables, literature, internships, courses, conferences,…). We learn to measure and evaluate research outputs. Let’s try to use a similar approach in teaching, whether remotely or after returning to in-person teaching.

All of this, of course, works better if this effort has systemic support and appreciation for the quality of instruction “from above”, i.e. from higher levels – from heads of departments or institutes or clinics, faculty management, the administrative units of faculties or the university. However, nothing can replace the specific commitment of individual instructors and their pedagogical work. It is not necessary to change the existing curriculum or organize a “teaching revolution” for quality distance learning. Even with a lack of time and resources and the constant overload of instructors, the quality of teaching can be significantly improved by applying the principles of evidence-based teaching (EBT). On the other hand, well-organized university instruction in accordance with EBT findings is a workload comparable to academic research.

Let’s dedicate the maximum amount of time in distance learning to the active work of students. Let’s cultivate frequent feedback in both directions. Let’s understand that a common solution to well-prepared issues and discussions on them among students will result in higher retention of the materials than the mere transfer of information. Let’s provide students with concrete learning outcomes as a motivating document that prevents many problems and prolongs active learning. And on this same list of verifiable, achievable, measurable, unambiguous, public and comprehensible assignments that we are satisfied with after completion, let’s add the transparent and fair evaluation of students. Let’s present students with a vision of how to be successful individuals in their fields and assist them in this. And we wish for all of you instructors the strength and ability to nurture your mental health and to enjoy your essential work as educators and leaders.